Translation of an interview by Titus Arnu, originally published on August 31, 2016, in the © Süddeutsche Zeitung

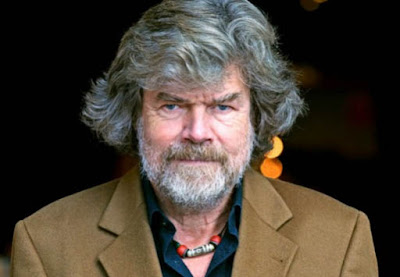

A hacker of summit crosses is currently haunting the Bavarian Alps: three times this summer, mountaintop crucifixes have been so badly damaged with an axe that they have had to be taken down, most recently on the Schafreuter (2102) in the Karwendel range. A case of religious hatred? And what value do summit crosses actually have from an alpinistic and philosophical point of view? We asked Reinhold Messner, 71, the most famous climber in the world.

|

| Reinhold Messner (c) Süddeutsche Zeitung |

SZ: You have climbed all the eight thousanders - and have probably visited almost all the summit crosses on the famous four-thousanders in the Alps. How do you relate to these things?

Messner: Choosing my words carefully here, they are not necessarily to my taste. But I would never take one down, and if somebody damages one, this is an act of vandalism. But I could personally do without any more summit crosses.

Why?

The cross is the ultimate Christian symbol, but it doesn’t belong on a summit, in my opinion. I’m not saying it’s an abuse, I'm just saying you shouldn’t hijack the mountains for religious ends. The mountains belong to everybody and shouldn’t be connected with or monopolised by a particular point of view. The mountains themselves have a certain sublimity – they don’t need a symbol of the supernatural. But there’s a solid cultural explanation for why summit crosses exist.

And what is that?

Summit crosses are a relatively recent phenomenon, dating back just over 200 years. At first, in this part of the world too, they were symbols of resistance to the Enlightenment: When the pious Tyroleans rose up against foreign rule of the Bavarians and French, they advanced their crosses as a protest against the French, who had been campaigning against the Catholic Church. After that, the matter took on a life of its own and crosses proliferated all over the Alps. You can revisit this history in my alpine museum in Bolzano, where we have an exhibit on summit symbology. In short, though, our mountains are well enough stocked-up with crosses already.

Don’t summit crosses make sense as a way of marking the highest point?

Many crosses don’t actually stand on the top of the mountain, but rather on subsidiary summits and and the like, where they can be easily seen from the valley. Before there were crosses, people marked summits by stacking up piles of stones, just to show that somebody had been there. And there were “weather crosses” to protect mountain dwellers against lightning and severe weather - I see this as part of alpine culture. Also summit books have a certain purpose: they tell one who has reached a summit and when. But it was only with the Enlightenment that summit crosses came. As symbols of the modern era, we now have mobile phone masts and TV antennas on mountaintops, which, admittedly, are even uglier, more invasive and obtrusive than crosses.

People have always projected fears, yearnings and religious feelings onto mountain peaks. Why is this?

It is striking that the great monotheistic religions all have strong connections to the mountains. Moses came down from Mount Sinai, after he received the Ten Commandments from God. Mohammed meditated in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, according to tradition, where he received his first revelation. Buddhism has its roots in northern India, at the foot of the Himalayas. And long before that, the summits were seen as the place of gods and demons. This is part of our cultural history, but still, in my view, one shouldn’t clutter the mountains with religious, political and other ideological symbols. These are mostly demonstrations of authority. They’re all about domination.

What do you mean?

Let me give two examples. In 1975, the Chinese allegedly dragged a bust of Chairman Mao all the way up Mount Everest, although I can’t confirm that from my visit to the summit in 1978. If the thing is there at all, it was buried under snow and ice long ago. As for Stalin, he allegedly had his likeness set up on Pik Communism (7495m) in Tajikistan, the highest peak in the former Soviet Union. Isn’t this totally absurd? Laying claim to mountains in this way has only one purpose: demonstrating the supposed authority of one person, or one nation, or one faith. It’s about conquest, misusing places that can be seen from afar, or making statements that have nothing to do with the mountains themselves.

But can’t you accept that people just like to have the summit crosses around - whether for religious reasons, or out of tradition, or just for a beautiful summit photo?

Yes, I can understand this but I don’t feel like joining in. I remember how the young folk in my home town of Villnöss used to drag wooden crosses up to the summit, at huge cost, and set them up there with all ceremony. I was never part of that, as I would rather be climbing – demonstrations of authority or faith have never been my thing.

In recent years, we’ve been seeing more and more Tibetan prayer flags on Alpine peaks, often with political messages such as "Free Tibet". What do you think?

Not much. I don’t mind if people hang out prayer flags in their own home. In fact, I have some at Schloss Juval, as I feel that I have a close connection to Buddhism. I have several times worked with the Dalai Lama on independence issues. But prayer flags don’t belong on alpine peaks any more than would crosses in the Himalaya.

Would you want to take down the summit crosses?

Of course not - the summit crosses we already have should stay where they are for historical reasons. And I would never excuse anybody who chopped a cross down, that's almost an act of terrorism. I prefer words as my weapons. But one is at liberty to ask whether summit crosses are as inseparable a part of our Christian culture as churches, cemeteries and weather crosses.

No comments:

Post a Comment